Relationship Between Blood Mercury Concentration and Waist-to-Hip Ratio in Elderly Korean Individuals Living in Coastal Areas

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

This study investigated the relationship between the blood mercury concentration and cardiovascular risk factors in elderly Korean individuals living in coastal areas.

Methods

The sample consisted of 477 adults (164 males, 313 females) aged 40 to 65 years who visited a Busan health promotion center from June to September in 2009. The relationship between blood mercury concentration and cardiovascular risk factors including metabolic syndrome, cholesterol profiles, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), was investigated. Variables related to blood mercury concentration were further evaluated using multiple regression analysis.

Results

The blood mercury concentration of the study population was 7.99 (range, 7.60 to 8.40) µg/L. In males, the blood mercury concentration was 9.74 (8.92 to 10.63) µg/L, which was significantly higher than that in females (7.21, [6.80 to 7.64] µg/L). The blood mercury concentration of the study population was related to several cardiovascular risk factors including low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (p=0.044), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (p=0.034), BMI (p = 0.006), waist circumference (p = 0.031), and WHR (p < 0.001). In males, the blood mercury concentration was significantly correlated with WHR in the multiple regression analysis.

Conclusions

In males, the blood mercury concentration was related to waist-to-hip ratio, which is a central obesity index and cardiovascular risk factor. Our finding suggests that cardiovascular disease risk in males was increased by mercury exposure via an obesity-related mechanism.

INTRODUCTION

The metal mercury is used in thermometers, fluorescent lamps and batteries; however, over-exposure to mercury is harmful to human health [1]. In aqueous ecosystems, this metal is converted into methylmercury, which accumulates in fish and shellfish. Contaminated fish and shellfish are the main source of mercury exposure in humans and methylmercury is readily absorbed by the alimentary tract. Dietary exposure of fertile women to mercury increases the risk of neurological problems in the fetus during pregnancy [2-4]. In 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommended that fertile women reduce their consumption of mercury-contaminated seafood [5]. In 2009, human biomonitoring (HBM) established two safety criteria for blood mercury levels: HBM I, 5 µg/L, an alert level under which no risk of adverse health effects, and HBM II, 15 µg/L, an action level above which an increased risk of adverse health effects does exist [6].

Wiggers et al. [7] observed that low level of exposure to mercury altered vascular activity and induced endothelial cell dysfunction in animals. De Marco et al, [8] observed that the blood mercury level of humans was significantly association with the plasma nitric oxide level, but the effect of mercury on cardiovascular disease has not established [9]. Indeed, Guallar et al, [10] reported that the mercury level in patients suffering from myocardial infarction was associated with the mortality rate in this group, whereas Yoshizawa et al. [11] did not observe this association. It is difficult to understand the effects of mercury exposure on cardiovascular disease because fish and shellfish contained unsaturated fats, which protect against cardiovascular disease and act in a manner opposite to the adverse effect of mercury exposure [12,13]. A recent study of mercury exposure and cardiovascular disease integrated the adverse effects of mercury exposure and the protective effect of unsaturated fats [14].

Busan, Korea is located in coastal area and has the highest standardized mortality ratio (SMR) for cardiovascular disease compared with other provinces in Korea: Busan, 31.6; Incheon, 26.5; Ulsan, 24.2; Deagu, 23.9; Daejeon, 20.3; Gwangju, 19.6; and Seoul, 18.7 [15]. We found that the mortality from cardiovascular disease was higher in coastal areas (Busan, Incheon and Ulsan) than inland (Deagu, Daejeon, and Gwangju) areas [15]. However, no study has evaluated the health effects of mercury exposure on the risk for cardiovascular disease in coastal areas. In Korea, research on mercury has been limited to evaluating the mercury exposure by region or investigating pathological mechanisms as heart rate variability [16-21]. Investigations in other countries have compared the cardiovascular disease risk of subjects with high and low level of mercury, although studies on factors that are intermediate between mercury levels and risk for cardiovascular disease are insufficient [22]. Therefore, this study evaluates the relationship between the mercury exposure level and risk for cardiovascular disease in Korea, by comparing blood mercury concentrations with presence and parameters of metabolic syndrome, including cholesterol profiles, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) and fasting blood sugar levels.

METHODS

I. Study Population

The samples recruited from subjects who had participated in Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) and consisted of 477 middle-aged people (40-65 years; 164 males, 313 females) who visited a health promotion center in Busan from June to September, 2009. All the participants were informed of the study purpose and provided consent for blood sampling and the use of a personal data. This study was performed after approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Dong-A Medical Center.

II. Questionnaire

A questionnaire survey was administered in face-to-face interviews. The questionnaire gathered information on demographic factors (sex and age), smoking status, drinking habits, menopause, and history of diseases.

III. Blood Sampling and Anthropometric Measurements

Blood was sampled after an 8-hour fast and the samples were transported to a diagnostic center in Seoul. The cholesterol profiles and fasting blood sugar levels were analyzed using an enzymatic method. Blood pressure was checked twice by a trained examiner after participants rested for 5 minutes in a sitting position. Waist circumference was determined with a measuring tape placed midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest during expiration. Hip circumference was measured at the level of the greater trochanters. The WHR equaled the waist circumference divided by the hip circumference. Metabolic syndrome was determined by the National Cholesterol Education Program - Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III) criteria, using the waist circumference for Koreans (males, 90 cm; females, 85 cm) [23].

IV. Measuring the Blood Mercury Concentration

The blood mercury concentration was analyzed using the double-amalgam method with cold vapor atomic absorption spectrometry (CV-AAS) using a mercury analyzer (SP-3DS, NIC, Tokyo, Japan). Blood samples were collected in an EDTA-treated 3 -mL vacuum tube, transported on dry ice and stored in a refrigerator at - 70℃. Before analysis, the blood samples were thawed slowly at room temperature and homogenized with a roller-mixer for 1 hour. The blood samples were premixed with 0.001 % L-cysteine solution, the hg-BHT, and the hg-MHT reagents (NIC, Tokyo, Japan) were added, and the sample was introduced into the analyzer. After the samples were heated at 650℃, the mercury in the samples was evaporated and captured by gold amalgam. The captured mercury was evaporated and introduced into a spectrometer by reheating gold amalgam at 700℃. The blood mercury concentration was determined by the value absorbed at 253.7 nm. The L-cysteine solution was produced by mixing 10 mg of L-cysteine and 2 mL of 60% nitric acid. A calibration curve was plotted by 2, 4, 6, and 8- ppb solutions made from a 1000 ppm mercury standard solution (Wako, Osaka, Japan) diluted with L-cysteine solution. External quality control was provided by the Korea Occupational Safety & Health Agency (KOSHA) and the German External Quality Assessment Scheme (G-EQUAS).

V. Statistical Analysis

Data on blood mercury concentrations had a leftwardskewed distribution and were analyzed using logarithmic transformation. The blood mercury concentration was compared with the cardiovascular risk factors including blood pressure, cholesterol profiles, BMI, waist circumference and WHR, using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The association between blood mercury concentration and cardiovascular risk factors was evaluated using multiple regression analysis. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

I. General Characteristics of the Study Population

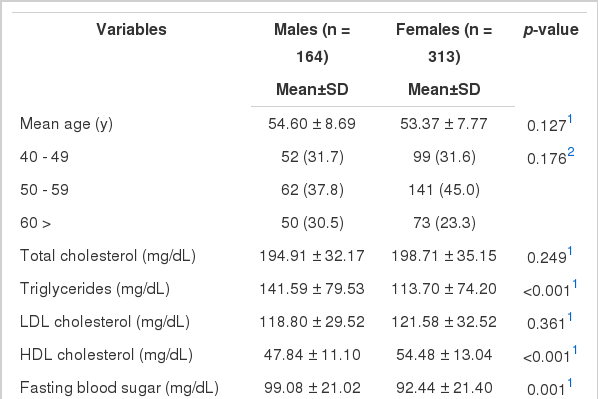

The study population consisted of 477 adults including 164 males and 313 females. The mean age of study population was 53.79 ± 8.11 years and that of male (54.60 ± 8.69) and female (53.37 ± 7.77) subjects did not differ significantly. The age distribution and frequency of fish intake of men and women did not differ, but smoking status and drinking habits differed significantly (Table 1).

II. Blood Mercury Concentration

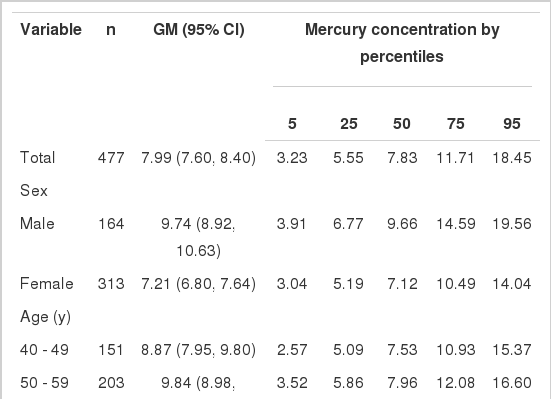

The blood mercury concentration of the study population, males and females were 7.99 (range 7.60 to 8.44), 9.74 (8.92 to 10.63) and 7.21 (6.80 to 7.64) µg/L, respectively. The blood mercury concentration of males was significantly higher than that of females. The blood mercury concentrations of subjects in their 40s, 50s, and 60s were 8.87 (7.95 to 9.80), 9.84 (8.98 to 10.71), and 9.06 (8.91 to 9.94) µg/L, respectively (Table 2).

III. Cardiovascular Risk Factors

Comparison of blood mercury with cardiovascular risk factors showed that low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, BMI, waist circumference and WHR differed significantly, whereas the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, total cholesterol, triglycerides, blood pressure, and fasting blood sugar levels did not differ in this regard. BMI and WHR were significant variables among men, whereas LDL cholesterol level, menopause, and WHR were significant variables among women (Table 3).

IV. Association between Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Blood Mercury Concentration

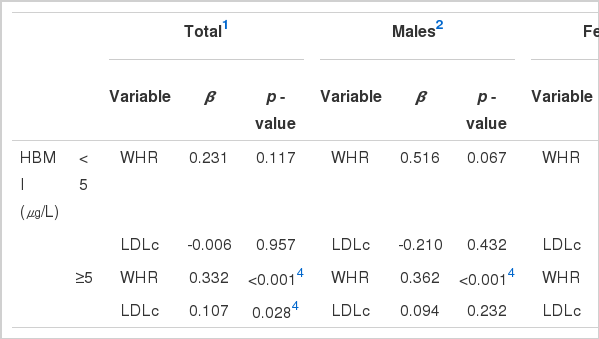

Multiple regression analysis showed that WHRs (p<0.001) and LDL cholesterol (p=0.028) levels for the group who met the HBM I criterion were associated with blood mercury concentration after adjusting for age, sex, alcohol intake, and smoking status (Table 4). Specifically, the WHRs of males whose scores met HBM I threshold were associated with their blood mercury concentration (p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the blood mercury concentration differed significantly according to the several cardiovascular risk factors as BMI, LDL cholesterol, waist circumference and WHR. By contrast, HDL cholesterol showed no correlation with blood mercury concentration. The WHRs of males were significantly related to their blood mercury concentrations. Therefore, males with heavy mercury exposure may be susceptible to cardiovascular disease based on their WHR.

Typically, hair, urine and blood are used to evaluate mercury exposure. The mercury level in hair and urine reflects long-term exposure, although the mercury concentration in hair samples is prone to error because of external contamination such as with dyes, and varies with length of the hair. It is inconvenient to collect urine samples to determine mercury levels, and the urine creatinine level should be 30-300 mg/dL [24]. Although blood mercury level reflects recent mercury exposure, it is used widely for monitoring the mercury exposure of population at risk and for comparison with other populations. The Second National Human Exposure and Biomonitoring Examination of Mercury measured the exposure level of 2369 Koreans at 3.80 (3.66 to 3.93) µg/L, whereas the Third Korean Health Examination Survey found a level of 4.15 (3.94 to 4.36) µg/L in 1997 adults [16-18]. The geometric mean of blood mercury concentration in our study was 7.99 (7.60 to 8.40) µg/L, which was higher than the range of 3.80 to 4.15 µg/L in the previous Korean National Studies. The blood mercury concentration of previous studies of coastal population was 6.54 to 8.63 µg/L [19,20], which is similar to the mean value in our study.

Mahaffey reported that the distributions of mercury levels in a single country differed by geographic location and high mercury level in coastal areas were a result of the ready access to fresh seafood [25]. The HBM has suggested two criteria for mercury exposure: HBM I as an alert level and HBM II as an action level [6]. The highest quartile of blood mercury concentrations (14.59 µg/L) in males corresponds to HBM II, and the population at risk for mercury exposure comprised one-quarter of the male population. The mean blood mercury level may have been higher if more participated in our study. Virtanen et al. [26] reported that Hallgren et al. observed no association between the mercury level and cardiovascular risk because females with low mercury concentrations participated in their study, and the distribution of mercury concentrations in the study population was too narrow to identify the association of mercury exposure with cardiovascular risk. In our study, blood mercury levels ranged from 1.48 to 45.54 µg/L and a sufficient numbers of subjects above the criterion for HBM II participated in our study.

Among the cardiovascular risk factors, BMI and WHR, indices of obesity differed according to mercury concentrations. BMI is related to general adiposity and WHR is related to central obesity [27]. In a multiple regression analysis, WHR was associated with blood mercury concentration, whereas BMI was not. Additionally, the WHRs of men were correlated with their mercury levels. This result concurred with a study of Brazilian natives in a mercury-contaminated area that found mercury exposure from fish consumption was not associated with BMI [28]. Hu et al. reported that the WHRs of men were significantly associated with cardiovascular disease risk, whereas BMIs were associated with increased cardiovascular risk in both sexes [27]. In a study of Faroe islanders and inhabitants of Nunavik who traditionally consume fish, mercury exposure was associated with blood pressure as cardiovascular risk factor in males only [29,30]. In a European study targeting adult men, an increased risk of mortality was observed in newly diagnosed patients with myocardial infarction with high mercury concentrations. Those results were consistent with our findings of significant association between blood mercury concentration and cardiovascular disease risk in males.

The mercury concentration was reported to be higher in males than in females. In our study, mercury concentrations were significantly higher in males than in females, and an association between mercury exposure and cardiovascular disease risk was observed in males. Blood mercury concentration was not significantly associated with menopause, and we postulate that estrogen has a limited effect on mercury levels. It is possible that this limited significance derived from differences in the alcohol intake and smoking status by sex, whereas fish consumption was excluded because no differences in the frequency of fish consumption according to sex were observed. Kim et al. reported that drinking alcohol affected mercury concentration [14], whereas Son et al. reported found no association between alcohol consumption and mercury concentration [17]. Smoking status has not been associated with mercury concentration. Therefore, the differences of mercury concentrations by sex require further investigation.

Metabolic syndrome is a cardiovascular risk factor and is related to obesity. We found that the metabolic syndrome was not correlated with mercury concentration. Park et al. [31] reported that those in highest quartile of hair-mercury concentration had an increased risk of metabolic syndrome compared with those in the lowest quartile. These findings were based on differences in the mercury concentrations in hair specimens, which were used as an index of previous exposure to mercury [32], or on the significance of differences between the lowest and the highest quartiles of mercury concentrations. In our results, waist circumference was the only variable of five diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome (NCEP ATP-III) associated with mercury level. Thus, metabolic syndrome was not related to mercury level because a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome must meet three additional diagnostic criteria.

Kim et al. [33] reported that urinary mercury in children was associated with serum cholesterol and suggested that heavy metal was as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. We found that a blood mercury concentration in males above HBM I was correlated with WHR as an index of central obesity. Based on this finding, we postulated that the risk for cardiovascular disease of men with a high mercury exposure was increased by WHR. However, a significant confounding effect, that obese subjects may eat more mercury-contaminated seafood resulting in a high mercury exposure, should also be considered. Dietary data are essential to answer this problem, but one weakness of our study was that its design did not include such data for analysis. A future study should examine dietary data and the adverse health effects of mercury exposure. In addition, no definite pathological mechanism has been identified to explain the relationship between the mercury level in males and their WHRs, an index of central obesity. Further investigations into the mechanisms related mercury exposure and central obesity or a cohort study of a population with heavy mercury exposure should contribute to our understanding of the effect of mercury on cardiovascular disease.

Notes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this study.

This article is available at http://jpmph.org/.