Perceived Environmental Pollution and Its Impact on Health in China, Japan, and South Korea

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

Environmental pollution is a significant global issue. Both objective (scientifically measured) environmental pollution and perceived levels of pollution are important predictors of self-reported health. The purpose of this study was to compare the associations between perceived environmental pollution and health in China, Japan, and South Korea.

Methods

Data were obtained from the East Asian Social Survey and the Cross-National Survey Data Sets: Health and Society in East Asia, 2010 (n=7938; China, n=3866; Japan, n=2496; South Korea, n=1576).

Results

South Koreans perceived environmental pollution to be the most severe, while Japanese participants perceived environmental pollution to be the least severe. Although the Japanese did not perceive environmental pollution to be very severe, their self-rated physical health was significantly related to perceived environmental pollution, while the analogous relationships were not significant for the Chinese or Korean participants. Better mental health was related to lower levels of perceived air pollution in China, as well as lower levels of perceived all types of pollution in Japan and lower levels of perceived noise pollution in South Korea.

Conclusions

Physical and mental health and individual socio-demographic characteristics were associated with levels of perceived environmental pollution, but with different patterns among these three countries.

INTRODUCTION

Due to economic and population growth, environmental pollution is a significant issue in Asia [1,2]. In Asia, China ranks the fifth worst for pollution, South Korea (hereafter Korea) eighth, and Japan last (14th) [1]. Many health impacts from environmental pollution have been reported. Air pollution has been shown to be associated with lung cancer [3], lung function [4], respiratory problems [5], and cardiovascular disease [6]. Water pollution has been linked to water-borne diseases [7] and chemical poisoning [8]. Noise pollution, in turn, is likely to increase the risks of cardiovascular disease, sleep disturbance, stress, and hearing impairment [9,10]. Previous studies have shown that both objective (scientifically measured) environmental pollution and perceived levels of pollution are important predictors of self-reported health [11,12].

Because of the fast economic growth and urbanization in China, the adverse impact of air and water pollution on individuals’ health has become an increasingly serious problem [13,14]. To respond to the air pollution issue, the Chinese government presented the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan in 2013 [15]. Studies measuring objective air pollution in China have shown increased risks for lung cancer [16], respiratory diseases [17], cardiovascular diseases, and adverse reproductive health [18]. Perceived environmental hazards, such as water pollution, negatively affect physical and mental health [14]. However, even in areas with extremely high objective levels of pollution, people are often not concerned about pollution [19].

Japan experienced severe water pollution in the 1960s, when its economy was rapidly growing [20]. Although the quality of the water has significantly improved, there are still some environmental issues remaining [20]. In southern areas of Japan, air pollution transported from China is an environmental concern [21]. Actual air pollution has been associated with health-related quality of life [22] and low birth weight [23] in the Japanese population.

Studies conducted in Korea have suggested that objective air pollution is associated with suicide [24], stroke [25], infant respiratory mortality [26], and asthma in children [27]. Air pollution is a significant public health issue in the Seoul metropolitan area [28]. Government regulations have contributed to reducing carbon monoxide levels in urban areas [24]. Yet, evidence-based policy regarding air pollution and health is lacking in Korea [29].

Few studies have examined the association between perceived environmental pollution and health in China, Japan, and Korea and how such perceptions differ among these three countries. The purpose of this study was to compare the association between perceived environmental pollution and health in China, Japan, and Korea in hopes of providing insights to inform successful future health interventions. It has been shown that individual factors, such as age and educational level, affect perceived levels of air pollution [30].

METHODS

Data

Data were obtained from the East Asian Social Survey and Cross-National Survey Data Sets: Health and Society in East Asia, 2010 (Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research [ICPSR] 34608). The cross-sectional retrospective data were collected from nationally representative samples through self-administered surveys and/or interviews. Detailed information about the study, including data collection procedures, is available at http://www.eassda.org/. The original collector of the data obtained ethical approval. The analysis of publicly available secondary data from the ICPSR did not require institutional review board review. The original collector of the data, ICPSR, and the relevant funding agency bear no responsibility for the use of the data or for interpretations or inferences based upon such uses.

Measures

Perceived environmental pollution

Perceived air/water/noise pollution was assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (1, very severe; 4, not severe at all), with lower scores indicating higher levels of perceived pollution.

Physical and mental health

The Short Form 12-Item survey (SF-12) measures physical and mental health functioning and well-being during the past 4 weeks [31]. The SF-12 produces 2 composite scores: a physical health composite scale (PCS) and a mental health composite scale (MCS), with a possible score range of 0 to 100 [32]. Higher scores indicate better health [33].

Socio-demographic characteristics

The following socioeconomic characteristics were analyzed: age, sex, marital status, education (years of schooling), employment status, and living in a large city.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the distribution of the outcome and independent variables. Comparisons were conducted using the Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Multiple regression analyses were conducted separately for China, Japan, and Korea to predict the levels of environmental pollution associated with self-reported physical and mental health and the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

RESULTS

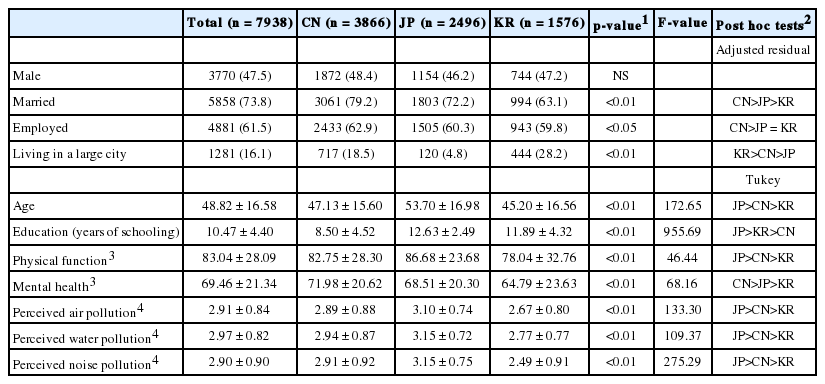

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants (n=7938; China, n=3866; Japan, n=2496; Korea, n=1576) and their levels of perceived environmental pollution. Approximately half of the participants were males (n=3770, 47.5%). Chinese participants were more likely to be married (n=3061, 79.2%) than Japanese participants (n=1803, 72.2%) or Korean participants (n=994, 63.1%) (p<0.01). Likewise, Chinese participants were more likely to be employed (n=2433, 62.9%) than Japanese participants (n=1505, 60.3%) or Korean participants (n=943, 59.8%) (p<0.05). Japanese participants were older (mean age, 53.70 years; standard deviation [SD], 16.98 years) than Chinese participants (mean, 47.13 years; SD, 15.60 years) or Korean participants (mean, 45.20 years; SD, 16.56 years) (p<0.01). Japanese participants reported higher levels of educational attainment (mean, 12.63 years; SD, 2.49 years) than Korean participants (mean, 11.89 years; SD, 4.32 years) or Chinese participants (mean, 8.50 years; SD, 4.52 years) (p<0.01). Japanese participants reported better physical functioning (mean, 86.68; SD, 23.68) than Chinese participants (mean, 82.75; SD, 28.30) or Korean participants (mean, 78.04; SD, 32.76), while Chinese participants reported better mental health functioning (mean, 71.98; SD, 20.62) than Japanese participants (mean, 68.51; SD, 20.30) or Korean participants (mean, 64.79; SD, 23.63) (p<0.01). Korean participants perceived all types of environmental pollution (air, water, and noise) to be the most severe, while Japanese participants perceived all types of environmental pollution to be the least severe (p<0.01).

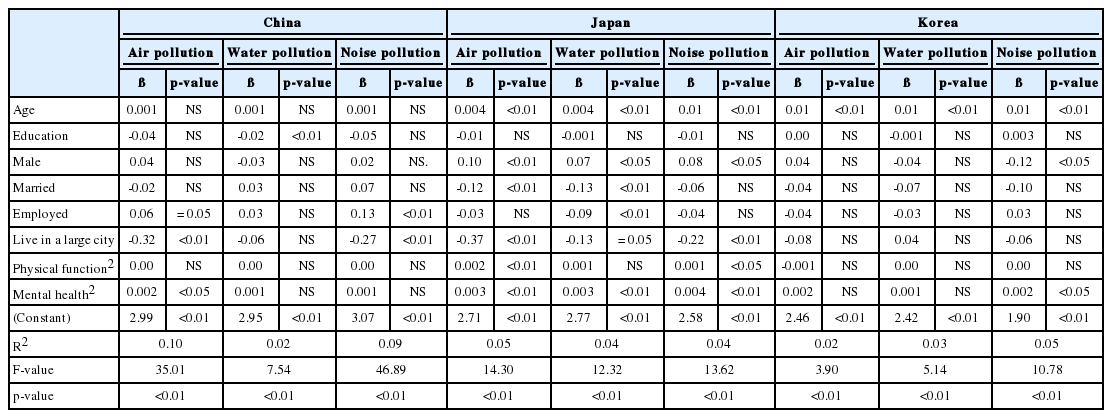

Table 2 presents the factors associated with perceived environmental pollution. In China, better mental health was associated with lower levels of perceived air pollution (p<0.05). Higher levels of education were associated with higher levels of perceived water pollution (p<0.01). Participants who were employed were more likely to report lower levels of noise pollution than those who were not employed (p<0.01). Participants who lived in a large city were more likely to report higher levels of air pollution and noise pollution (p<0.01).

In Japan, better mental health was associated with lower levels of perceived air, water, and noise pollution (p<0.01). Better physical health was associated with lower levels of perceived air (p<0.01) and noise (p<0.05) pollution. Older participants were more likely to perceive lower levels of all types of pollution than younger participants (p<0.01). Male participants were more likely to perceive lower levels of all types of pollution than female participants (p<0.01 for air pollution, p<0.05 for water and noise pollution). Married participants were more likely to perceive higher levels of air and water pollution than unmarried participants (p<0.01). Employed participants were more likely to perceive higher levels of water pollution than unemployed participants (p<0.01). Participants living in a large city were more likely to report higher levels of air and noise pollution than those not living in a large city (p<0.01).

In Korea, better mental health was associated with lower levels of perceived noise pollution (p<0.05). Male participants were more likely to perceive higher levels of noise pollution (p<0.05). Older age was associated with lower levels of air, water, and noise pollution (p<0.01).

DISCUSSION

This study examined perceived environmental pollution and health in China, Japan, and Korea. There are three main findings. First, Koreans perceived environmental pollution to be the most severe, while Japanese participants perceived environmental pollution to be the least severe. Second, although the Japanese did not perceive environmental pollution to be very severe, their self-rated physical health was significantly related to perceived environmental pollution, while the corresponding relationships were not significant for the Chinese or Korean participants. Third, better mental health was associated with lower levels of perceived air pollution in China, lower levels of perceived all types of pollution in Japan, and lower levels of perceived noise pollution in Korea.

The results of this study suggest that Koreans believe that pollution is the most severe, while Japanese believe that pollution is the least severe. This is not necessarily reflective of the objective air pollution levels in these countries. According to a WHO report on air pollution [34], China has the most severe air pollution, whereas Japan has the least severe air pollution. As for Korea, its residents perceive pollution to be the worst in their country, when in fact their country has better overall pollution than China. In Korea, there are concerns about air pollution caused by dust transported from China and/or Mongolia [35]. Pollution originating outside of one’s own country might affect perceived pollution in one’s home country.

Interestingly, although subjective and objective levels of pollution are not particularly severe in Japan compared to China and Korea, the self-reported physical health status of Japanese was more likely to be associated with perceived pollution than that of Chinese or Koreans. Since Japan started industrialization earlier than China and Korea, environmental pollution became an issue in the 19th century in Japan [36]. In 1967, Japan enacted the Basic Law for Environmental Pollution Control [36]. Since then, Japan has made several public efforts to reduce environmental pollution. The relatively long history of policies aiming to control environmental pollution might affect the high expectations of Japanese citizens for a clean environment and, as a result, the environmental pollution that they perceive might have an impact on their self-rated health.

Finally, mental health was found to be related to different kinds of pollution in each country: air pollution in China, all types of pollution in Japan, and noise pollution in Korea. However, this study does not explain the reason for this variation. Previous studies have shown that air, noise, and water pollution can affect mental health [37,38]. However, little is known about country-level variations in mental health and different types of environmental pollution. Future research should examine how different types of perceived environmental pollution are associated with mental health in different countries, in order to better understand mental health care related to perceived environmental pollution.

Both perceived and objective environmental pollution are important determinants of perceived and actual health status. Perceived pollution is associated with perceptions of health risks [39], and objective levels of environmental pollution are also associated with several health outcomes, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mental health issues [40]. This study adds new knowledge about perceived environmental pollution and health in China, Japan, and Korea, and these findings may be applicable beyond these three countries. Based on this comparison among three countries, perceived and objective levels of environmental pollution are not necessarily similar to each other. Levels of perceived environmental pollution are not always correlated with self-reported health status. Individual characteristics such as age, educational attainment, sex, marital status, employment status, and residence area (urban or non-urban) were also associated with perceived environmental pollution. Country-level variations were also found in the types of environmental pollution associated with mental health, and in individual characteristics affecting perceived environmental pollution.

These data are cross-sectional and limited in terms of their ability to allow causal inferences to be made among variables. The degree of perceived environmental pollution and health status varied depending on the residence area of the participants. Although the type of living environment (urban or not) was controlled for, variations in the levels of environmental pollution among urban areas within a country may be a source of potential bias in this study. Because the main focus of the questionnaire was chronic non-communicable diseases and their impact on lifestyle issues, the available information related to environmental pollution is limited. The dataset used for the current study does not include any objective measures of environmental pollution. Future research should examine the relationship between objective and perceived environmental pollution. Furthermore, the explanatory power of multiple regression is very low. In addition, the beta coefficients related to mental health were small.

To the best of our knowledge, this project is the first to compare these three countries regarding perceived environmental pollution and its impact on health. It is important to compare these three countries because successes in one country could be a potential platform for successes in other countries. Lastly, since pollution is a global issue, it is essential for countries within a region to work together to tackle the issue. This study contributes to practice and future research that may help to improve health in relation to perceived environmental pollution.

This study examined the associations between perceived environmental pollution and health in China, Japan, and Korea. Physical and mental health and individual socio-demographic characteristics were associated with levels of perceived environmental pollution, but in different patterns among these three countries. These three countries have different histories of governmental efforts to improve environmental pollution. Each country has different target populations who need interventions regarding perceived environmental pollution and its impact on health. While residents are likely to benefit from reducing exposure to environmental pollutants, dealing with objective environmental pollution will not be sufficient to improve the overall mental and physical health of the population. Environmental issues are a public health concern. Therefore, perceived environmental pollution needs to be addressed by governments and other organizations that tackle pollution issues, perhaps through educating citizens about pollution and ways to minimize exposure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project used publicly available secondary data from ICPSR. The East Asian Social Survey and the Cross-National Survey Data Sets: Health and Society in East Asia, 2010 were funded and conducted, and the data made publicly available, by the ICPSR. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.