Malaria Risk Factors in Kaligesing, Purworejo District, Central Java Province, Indonesia: A Case-control Study

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

Malaria remains a public health concern worldwide, including Indonesia. Purworejo is a district in which endemic of malaria, they have re-setup to entering malaria elimination in 2021. Accordingly, actions must be taken to accelerate and guaranty that the goal will reach based on an understanding of the risk factors for malaria. Thus, we analysed malaria risk factors based on human and housing conditions in Kaligesing, Purworejo, Indonesia.

Methods

A case-control study was carried out in Kaligesing subdistrict, Purworejo, Indonesia in July to August 2017. A structured questionnaire and checklist were used to collect data from 96 participants, who consisted of 48 controls and 48 cases. Univariate, bivariate, and multivariate analyses were performed.

Results

Bivariate analysis found that education level, the presence of a cattle cage within 100 m of the house, not sleeping under a bednet the previous night, and not closing the doors and windows from 6 p.m. to 5 a.m. were significantly (p≤0.25) associated with malaria. Of these factors, only not sleeping under a bednet the previous night and not closing the doors and windows from 6 p.m. to 5 a.m. were significantly associated with malaria.

Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that potential risk factor for Malaria should be paid of attention all the time, particularly for an area which is targeting Malaria elimination.

INTRODUCTION

Malaria has received much attention from the public health sector in most tropical countries across the world due to the difficulties in eliminating malaria and the fluctuations in malaria cases each year. During 2015 to 2016, malaria cases increased by 5 million, and were spread among 91 countries across the globe, with 445 000 deaths due to malaria in 2016 [1]. While Indonesia has generally succeeded in reducing the number of malaria cases over the last 5 decades [2], malaria still remains endemic in some regions, particularly in the eastern part of Indonesia, despite the unexpected achievement of malaria elimination [3]. Purworejo District is an area on the island of Java where malaria becomes endemic. They have failed to achieve malaria elimination by 2015. After that, 2021 has set up as the next target for entering Malaria elimination in Purworejo [4]. Nevertheless, due to the geographical position of Purworejo, which borders other endemic districts; environmental changes; and high mobility among residents, Purworejo needs regular assessments to maintain its malaria caseload below the requirement.

One strategy to combat malaria is through addressing the epidemiologic triad, which refers to the host, agent, and environment [5,6]. The agent of malaria is Plasmodium parasites, which consist of 5 species: Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium malariae, and Plasmodium knowlesi [1,7]. These parasites are transferred to humans (the secondary host) through bites of female Anopheles mosquitos (the definitive host) [8]. Both the host and the agent are influenced by environmental factors, such as climactic conditions [9], housing conditions [10], soil type, vegetation index, distance to a water source [11], and movements of people (most notably, urbanization and migration) [9]. As a holistic system, the epidemiologic triad could be used in malaria eradication by targeting one of its elements to stop malaria transmission. However, although malaria interventions have been performed based on this method, transmission still occurs.

As a district in which targeted to entering malaria elimination in 2021, it is important to observe the risk factors for malaria in Purworejo, as such factors could contribute to continued transmission. With this background in mind, the present study explored malaria risk factors referring to the epidemiologic triad. Human and housing conditions were assessed in this case-control study in Kaligesing, Purworejo, Indonesia.

METHODS

Study Site

Extensive research has been conducted on malaria in Indonesia, including in Purworejo [12-14]. Despite eradication efforts, the disease still occurs due to human and environmental dynamics. Accordingly, this study analysed the risk factors for malaria in Kaligesing, Purworejo, Indonesia. Kaligesing consists of 21 villages with 34 028 residents spread out across 74.74 km2. It is adjacent to Kulonprogo, Yogyakarta. The majority of Kaligesing comprises forest, moor, and copse areas that support the breeding of mosquitos that transmit malaria.

Study Design and Sample

This was a quantitative study with a case-control design. The case population comprised residents who were aged 17-55 years, had resided in Kaligesing for at least 1 year, and were confirmed to be positive for malaria through a blood sample analysis at the laboratory of the Kaligesing Public Health Centre (PHC) during January-December 2016. The control population included residents (with a minimum of 1 year of residence) who were confirmed to be negative for malaria through a blood sample analysis at the laboratory of the Kaligesing PHC during the same period and were able to participate in the study. We also required that the controls did not live with the cases to avoid information bias. Children and pregnant women were excluded.

Participant Selection

The sample size was calculated using the EpiTools epidemiological calculator for case-control studies (http://epitools.ausvet.com.au/content.php?page=case-controlSS), with a 0.33 expected proportion exposed in the controls, an assumed odds ratio of 3.13 (confidence interval, 1.61 to 6.07) based on the the previous research [15], a confidence level of 0.95, and a desired power of 0.80. Using these assumptions, the minimum sample size for the case was calculated to be 48. We established a 1:1 ratio between cases and controls. Correspondingly, a total of 96 participants were recruited, consisting of 48 cases and 48 controls. Consecutive sampling was applied to select the participants.

Research Instruments

A structured questionnaire and checklist, which were developed by the research team, were used to collect the data. The questionnaire was divided into 2 sections. Section 1 contained demographic information about the respondents, including name, age, sex, duration of residence, education, and occupation. Section 2 contained questions about risk factors, such as the presence of wire netting in the ventilation, the presence of a cattle cage, the condition of the ceiling of the residence, bednet utilization, behavior regarding closing windows and doors, and repellent utilization. A checklist was used to observe the real condition of variables such as wall type and condition, the presence of wire netting, the presence of a cattle cage, and ceiling condition.

Oral and written explanations were given to the participants about the study, including the freedom to discontinue participation in the study at any time without punishment. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before the study was started.

Analysis

Univariate, bivariate, and multivariate analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Univariate analysis was used to visualize the proportional distribution of all variables. The bivariate analysis was performed using the chi-square test and the Fisher exact test, with a significance level of p<0.05. These tests were used to evaluate relationships between variables. For dichotomizing the characteristics of occupation and education level, we used the following classifications. At risk occupations included participants who worked as a laborer, sugar maker, farmer, or soldier, and low-risk occupations included being a housewife, student, trader, private-sector worker, tailor, or civil servant. People with no formal education or who had only graduated from primary school or junior high school were considered to have a low level of education. People who had graduated from senior high school or higher were considered have a high level of education.

The final step was multivariate analysis. Variables with p≤0.25 in the bivariate analysis were entered into the multivariate analysis. Logistic regression was employed to illustrate the relationships between malaria positivity and multiple risk factor variables.

Ethical Considerations

This research was approved by the Department of Public Health, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan. A research permit was requested from the local health authorities (the Kaligesing Public Health Service and the Purworejo District Health Office).

RESULTS

Socio-demographic Characteristics

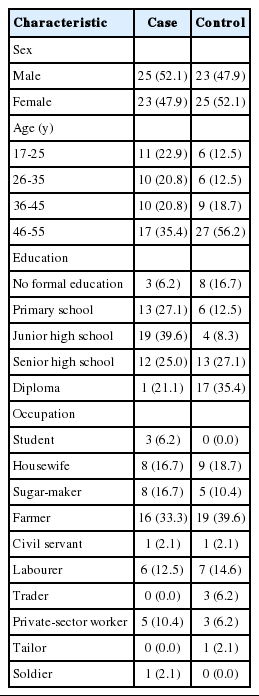

A total of 96 people participated in this study, consisting of 48 controls and 48 cases. Among the participants, 50% were female and 50% male. The majority of the respondents were between 46 and 55 years of age. Most of the participants had graduated from junior high school (39.6%) or senior high school (25.0%). Almost 40% of the participants worked in the private sector. Detailed information is presented in Table 1.

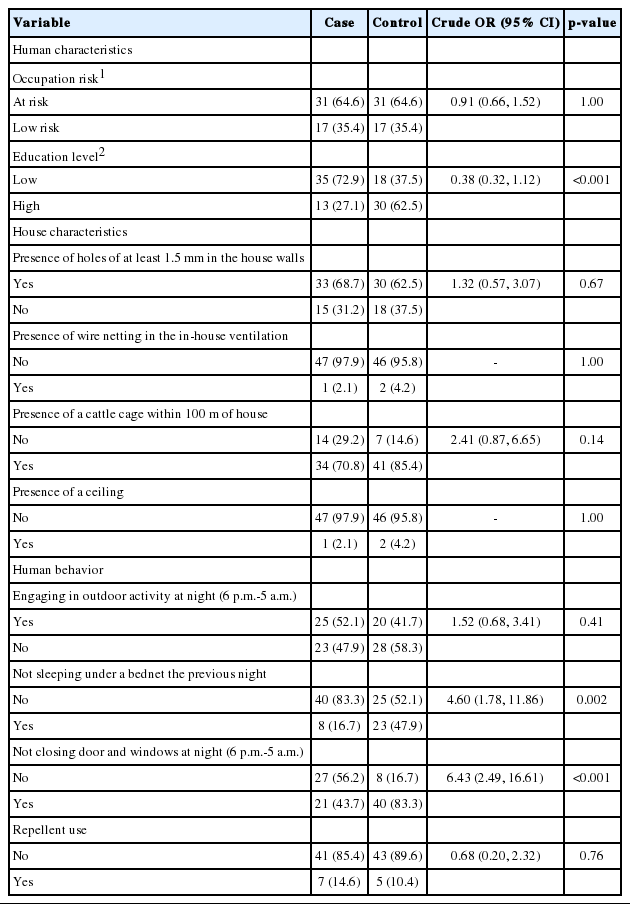

Associations between malaria and risk factor variables

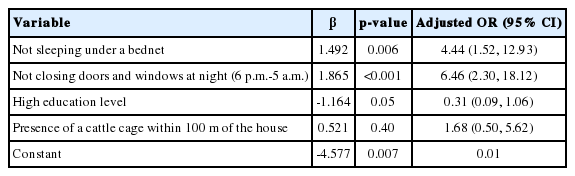

In this study, we explored the associations of 10 variables in 3 categories (human characteristics, house characteristics, and human behaviour) with malaria positivity. Four of these variables were statistically significantly associated with malaria positivity at the p≤0.25 level: education level, the presence of a cattle cage within 100 m from the house, not sleeping under a bednet the previous night, and not closing the doors and windows from 6 p.m. to 5 a.m. Three variables were did not show any significant findings in the bivariate analysis (Table 2): occupation risk, the presence of wire netting in the in-house ventilation, and the presence of the ceiling. The bivariate analysis is presented in Table 2. In the multivariate analysis, only 2 variables remained statistically significantly associated with malaria at the p≤0.01 level: not sleeping under a bednet the previous night and not closing the doors and windows from 6 p.m. to 5 a.m. (Table 3).

Bivariate analysis of malaria positivity vs. human characteristics, house characteristics, and human behaviours in Kaligesing, Purworejo, Indonesia

DISCUSSION

Malaria is a major problem in public health across the globe, predominantly in tropical countries such as Indonesia, due to the climactic, environmental, and human characteristics that support malaria transmission. In Indonesia, Purworejo is a district on the island of Java in which malaria was endemic. This district is part of the Menoreh hill region, where malaria has sometimes had a very high prevalence [11]. Kaligesing is a subdistrict of Purworejo that has been struggling with malaria, as it is adjacent to other endemic districts such as Kulonprogo, which also has a high prevalence of malaria [11]. This aspect of the location of Kaligesing makes it challenging to combat malaria in this subregion [14]. In this study, we assessed malaria risk factors through 10 variables. Based on our analysis, we established 2 variables as potential risk factors for malaria in Kaligesing-Purworejo: not sleeping under a bednet the previous night and not closing the doors and windows from 6 p.m. to 5 a.m.

Sleeping under a bednet is a technique to protect against mosquito bites. In this study, people who slept under a bednet had lower odds (4.6 times) of having malaria than those who did not. In Purworejo, 3 malaria vectors have been reported: Anopheles aconitus, Anopheles maculatus, and Anopheles balabacensis. An. maculatus, which mostly feeds at night and inside and outside the house [17], has been found in Menoreh Hills [18]. This characteristic of the vector may explain why sleeping under a bednet was a significant risk factor in the research area. This finding is confirmed by malaria research in The Gambia that found that using a bednet the previous night significantly reduced the odds of contracting malaria [19].

Concerning bednet use, the Purworejo health office is already taking proper actions by providing the residents with bednets to prevent malaria. This is related to the policy of the Indonesian government through the Ministry of Health to eliminate malaria on Java Island by 2015, including in Purworejo. To achieve this goal, many actions were carried out, including the use of long-lasting nets for malaria prevention and vector control [19,20]. Accordingly, the ownership of bednets in the research area seems to be quite high. However, compliance with sleeping under a bednet must improve.

The second risk factor was closing the doors and windows from 6 p,m. to 5 a.m. This variable relates to the habits of the vector and its likelihood of entering houses. In this study, ‘keeping closed’ was defined as ensuring the absence of any entrance access for the vector, including small holes in the windows and doors. Research into malaria vectors in the Asia-Pacific region has indicated that An. maculatus, which is the primary vector in Kaligesing, tends to rest outdoors (exophilic). Meanwhile, its activity starts in dusk, extending into the night [17]. Accordingly, keeping the windows and doors closed from dusk till the morning is essential to prevent the vector from entering the house.

An unexpected finding emerged from this research regarding protective factors. We discovered three variables did not show any significant findings in the bivariate analysis to: occupation, the presence of wire netting in the in-house ventilation, and the presence of a ceiling in the house. Although occupation is usually found to be a risk factor for malaria, in this research it was found could be a protective factor. We surmise that this finding was due to information bias from the participants. As shown in Table 1, the majority of participants worked in the private sector or as farmers. Those two occupations usually do not involve permanent positions and are seasonal. People in urban areas often switch jobs, suggesting that the information regarding the participants’ occupation was not accurate.

The next variable which found as a protective factor was the usage of repellent. Similarly, we surmise that factor was found to be protective due to aspects of the data acquisition process. We asked respondent with using mosquito repellent at night. It could be translated by respondent merely when they were sleep. Even though, repellent must also be applied if doing other activities at night. Accordingly, this potentially raises the issue of recall bias because we couldn’t observe their practice on using mosquito repellent, particularly in how frequent they were.

Malaria still exists in Kaligesing-Purworejo. Among the risk factors in this study, only not sleeping under a bed net and not keeping the windows and door closed from dusk till morning were significantly associated with malaria. However, this research may have 2 limitations. First, the risk factors included are related to human factors and a small part of the environment, while according to the concept of the epidemiologic triad, infectious disease transmission occurs due to 3 aspects: host, agent, and environment [6]. The second limitation is related to unanticipated recall bias. As a result, some common risk factors became protective factors.

Education was evaluated in this study, as knowledge about malaria has been widely reported to be a risk factor. However, in this study, education level was not found to be a risk factor for malaria. People in Purworejo have been exposed to malaria for several decades, but they have also been exposed to many malaria programs. Accordingly, even though many did not have high levels of formal education, they may have had comparable levels of malaria knowledge. However, it seems that people do not turn their knowledge into practice in terms of malaria prevention. This is supported by research that has shown that knowledge does not necessarily translate into good practice [21].

Considering the results of our research, we suggest that future research should comprehensively assess the 3 components of the epidemiologic triad: host, agent, and environment. Second, anticipating recall bias is needed in retrospective studies, underscoring the importance of considering local social conditions. Finally, local health authorities must continue the bednet program because bednets were proven to help protect people from malaria.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Purworejo District Health Office and Kaligesing Public Health Centre for helping us during the research. We also wish to thank all the participants who contributed to this study.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.