Annual Endovascular Thrombectomy Case Volume and Thrombectomy-capable Hospitals of Korea in Acute Stroke Care

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

Although it is difficult to define the quality of stroke care, acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients with moderate-to-severe neurological deficits may benefit from thrombectomy-capable hospitals (TCHs) that have a stroke unit, stroke specialists, and a substantial endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) case volume.

Methods

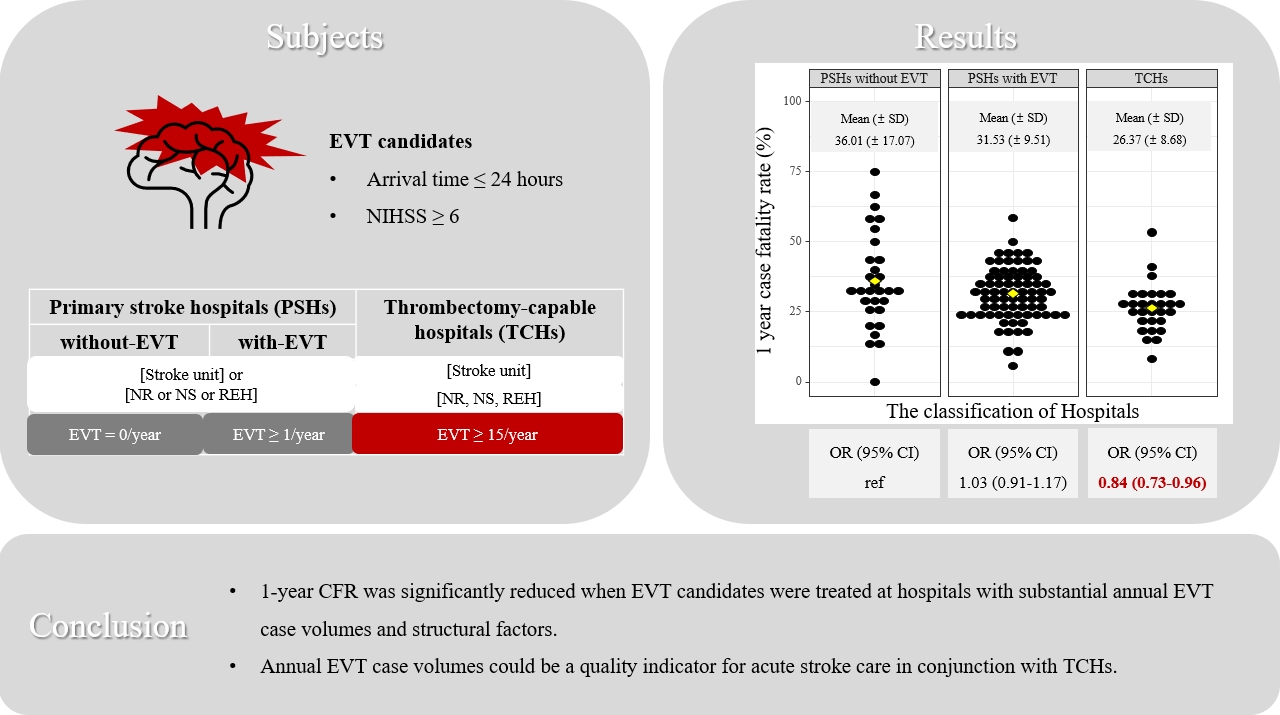

From national audit data collected between 2013 and 2016, potential EVT candidates arriving within 24 hours with a baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score ≥6 were identified. Hospitals were classified as TCHs (≥15 EVT case/y, stroke unit, and stroke specialists), primary stroke hospitals (PSHs) without EVT (PSHs-without-EVT, 0 case/y), and PSHs-with-EVT. Thirty-day and 1-year case-fatality rates (CFRs) were analyzed using random intercept multilevel logistic regression.

Results

Out of 35 004 AIS patients, 7954 (22.7%) EVT candidates were included in this study. The average 30-day CFR was 16.3% in PSHs-without-EVT, 14.8% in PSHs-with-EVT, and 11.0% in TCHs. The average 1-year CFR was 37.5% in PSHs-without-EVT, 31.3% in PSHs-with-EVT, and 26.2% in TCHs. In TCHs, a significant reduction was not found in the 30-day CFR (odds ratio [OR], 0.92; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.76 to 1.12), but was found in the 1-year CFR (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73 to 0.96).

Conclusions

The 1-year CFR was significantly reduced when EVT candidates were treated at TCHs. TCHs are not defined based solely on the number of EVTs, but also based on the presence of a stroke unit and stroke specialists. This supports the need for TCH certification in Korea and suggests that annual EVT case volume could be used to qualify TCHs.

INTRODUCTION

The implementation of endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) substantially improved the overall outcome of patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) due to large vessel occlusion (LVO) [1–5]. EVT rapidly became the standard of care in clinical practice [6–9]. However, a gap between evidence and practice still exists in acute stroke care [10]. EVT is a viable option only for AIS patients with LVO who have sufficient salvageable tissue [11], but it is impossible to confirm whether vascular occlusion is present at the pre-hospital stage [12]. Additionally, EVT is a resource-demanding treatment that requires a dedicated team of vascular neurologists, interventionalists, and technicians available 24 hr/day, 7 day/wk [13]. Performing EVT in all hospitals is, therefore, not feasible. The above difficulties show that it is necessary to have designated thrombectomy-capable hospitals (TCHs) and for the overall stroke system of care (SSOC) to be regionally designed in order to improve the outcome of AIS patients. The SSOC includes the multifaceted organization of pre-hospital and intra-hospital resources [14,15].

To organize regional SSOCs, it is first necessary to distinguish between hospitals that can perform EVT with high quality and those that do not. In the United States, the Joint Commission certifies a thrombectomy-capable stroke center as one that performs more than 15 EVT cases per year [16,17]. There are 2 paradigms for constructing a transport system in SSOC. First, the mothership (MS) model is a strategy to transfer EVT candidates directly to a TCH even if they are a little far away. Second, the drip-and-ship (DS) model is to send patients to the nearest hospital and transfer them to a TCH when EVT is required. According to a systematic review of studies to date, EVT candidates might benefit from the MS model as compared to the DS model [18]. In addition, the MS model may allow an efficient organization of on-call staff, intramural patient flow, stroke unit, institutional protocol, and quality improvement activities in each region [18,19].

In Korea, despite the widespread availability of EVT even in hospitals with low stroke volume, a TCH-based SSOC still has not been established [20–22]. Quality of care can be classified in terms of structure, process, and outcome [23]. In acute stroke care, structure refers to material resources (such as stroke units) and human resources (such as stroke specialists), process refers to the implementation rate of diagnosis and treatment (such as the annual EVT case volume), and outcome refers to the effects of care through the degree of dysfunction or death [10]. When designating and qualifying TCHs, it is important to comprehensively consider the quality of care in terms of these described measures. The Acute Stroke Quality Assessment Program (ASQAP) has been promoted since 2006 to improve the quality of care provided to acute stroke patients. The ASQAP reported that the quality of care had improved gradually compared to the beginning of implementation. However, most hospitals have achieved more than 90% in process indicators, making it difficult to identify variations between hospitals and to encourage quality improvement [24]. The annual EVT case volume has been known to be associated with a favorable prognosis in AIS [25–29]. Therefore, when selecting TCHs, the annual EVT case volume will help to further distinguish the quality of care between hospitals.

This study aims to suggest using the annual EVT case volume as an indicator for designating TCHs for acute stroke care. To this end, the ASQAP data between 2013 and 2016 were used to analyze how the case-fatality rate (CFR) of AIS patients varies according to hospitals’ annual EVT case volume and structural factors (the presence of a stroke unit and stroke specialists, including those in the field of neurology, neurosurgery, and rehabilitation medicine).

METHODS

Study Population

We utilized the ASQAP data, which comprise an anonymized national dataset merged from the claims data of the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service and the National Health Insurance Service, as well as data from the Clinical Research Collaboration for Stroke in Korea [30]. The study population consisted of all patients who were hospitalized for acute stroke from March to May 2013, from June to August 2014, and the second half of 2016 in the fifth, sixth, and seventh ASQAP data. The data were collected from all hospitals that reported more than 10 cases of AIS patients admitted during the defined data collection period.

The ASQAP data included all AIS patients admitted via the emergency department within 7 days of symptom onset and diagnosed with code I63 of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) [31]. For the current study, our inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) time of symptom onset, and (2) clinical severity of stroke symptoms [32]. We analyzed AIS patients who arrived ≤24 hours from symptom onset with a baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score ≥6 points, which represents moderate-to-severe neurological deficits [33,34]. We also included patients who were transferred. Out of 35 004 patients diagnosed with the ICD-10 code I63, 7954 patients were finally included in the analysis as EVT candidates.

Variables

Since annual EVT case volume has been known to be associated with a favorable prognosis in AIS patients [25–29], this factor was used as an important criterion for classifying hospitals. For the purposes of this study, we utilized the minimum requirement of 15 case/y used by the United States Joint Commission for their thrombectomy-capable stroke center certification process [16,17]. First, TCHs were defined as hospitals that performed a minimum of 15 EVTs per year and had a stroke unit with stroke specialists (at least 1 specialist in each of the neurology, neurosurgery, and rehabilitation medicine departments). Hospitals that either did not meet the minimum case count, or did not have a stroke unit with stroke specialists were classified as primary stroke hospitals (PSHs). Among these, hospitals that had never conducted an EVT during the data collection period were classified as PSHs-without-EVT, while those that had were defined as PSHs-with-EVT. The CFR was used as the observable outcome variable, representing the proportion of patients who died among the patients who had been enrolled; specifically, the CFR at 30 days and at 1 year. The 1-year CFR was considered as the primary outcome in this study. The 1-year CFR could be used as surrogate index for 3-month functional outcomes [35].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and graphical analyses were conducted with R version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Multilevel logistic regression was used with adjustments made with a random hospital-level intercept for the patient’s age, sex, comorbidity index, and NIHSS score. In the analysis, age and NIHSS were analyzed continuously, and sex and Charlson comorbidity index were analyzed dichotomously. Hospital-based registries such as ASQAP are inherently hierarchical; patients are nested within hospitals. Through multilevel analysis, both the patient-level and hospital-level characteristics of the variations in outcome can be considered [36]. The proportion of variance at the hospital level was estimated using the intraclass correlation coefficient. The fit of the model was evaluated with a −2 log-likelihood score. Finally, 2 multilevel logistic models were constructed in order to estimate the 30-day and 1-year CFRs, according to the hospitals’ classifications: PSHs-without-EVT, PSHs-with-EVT, and TCHs.

Ethics Statement

This observational study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (No. X-1902-522-902).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics of Endovascular Thrombectomy Candidates

During the data collection period (fifth through seventh), 1164 patients underwent EVT among 7954 moderate-to-severe AIS patients; 63.3% were over 70 years old and 51.8% were male. The distribution of admitted patients by hospital classification was as follows: 7.1% in PSHs-without-EVT, 52.4% in PSHs-with-EVT, and 40.5% in TCHs. Of the 7954 subjects, 1063 (13.4%) died within 30 days, and 2362 (29.7%) died within 1 year of admission. The CFR was the highest in PSHs and the lowest in TCHs (Table 1). The results classified by annual EVT case volume are presented in a Supplemental Material 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Hospitals: Primary Stroke Hospitals (PSHs)-without-endovascular Thrombectomy (EVT), PSHs-with-EVT, and Thrombectomy-capable Hospitals

A total of 177 hospitals were included in the analysis: 64 PSHs-without-EVT, 84 PSHs-with-EVT, and 29 TCHs. Stroke units were installed in 72 hospitals. The mean numbers of moderate-to-severe AIS patients by hospital classification were 8.8 in PSHs-without-EVT, 48.2 in PSHs-with-EVT, and 115.0 in TCHs. The mean numbers of EVT cases were 0 in PSHs-without-EVT, 8.8 in PSHs-with-EVT, and 35.1 in TCHs (Table 2).

The 30-day and 1-year Case-fatality Rate by Hospital Classification

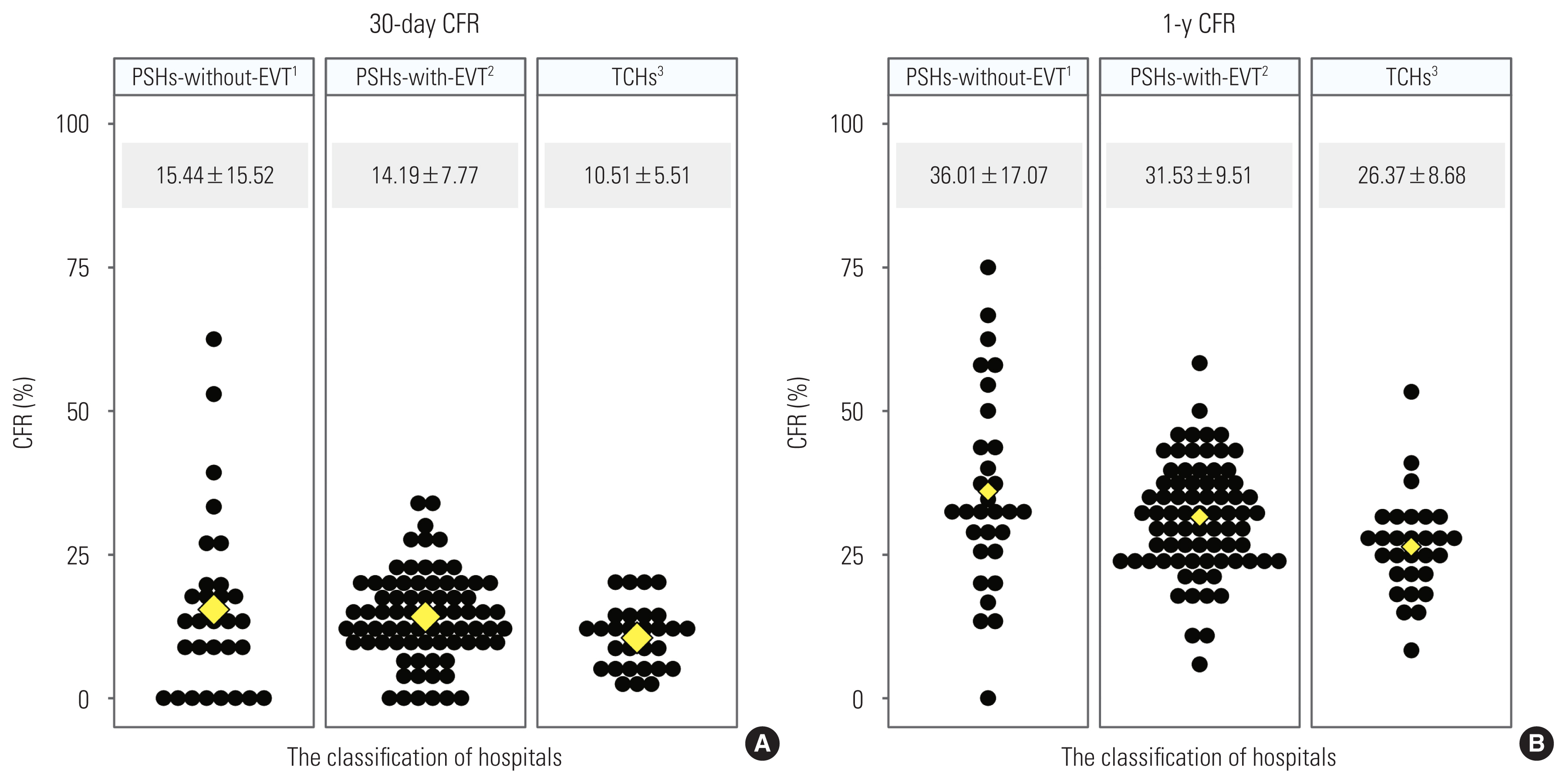

Figure 1 presents variations within and between hospital groups. Of the 177 hospitals, 42 hospitals, which had less than 5 suspected AIS patients, were excluded from the hospital sample for final analysis. TCHs had the lowest 30-day (10.51%) and 1-year (26.37%) CFRs, while PSHs-without-EVT had the highest 30-day (15.44%) and 1-year (36.01%) CFRs. Moreover, TCHs had less variation between their 30-day (standard deviation [SD], 5.51%) and 1-year (SD, 8.68%) CFRs, while PSHs-without-EVT had greater variation between their 30-day (SD, 15.52%) and 1-year (SD, 17.07%) CFRs, even with outlier hospitals were removed.

(A) 30-day and (B) 1-year case-fatality rate (CFR) of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) by the classification of hospitals. Each black dot represents the proportion of AIS patients who died in each hospital. Yellow diamonds represent the average of CFR by the classification of hospitals. Values are presented as mean±standard deviation. 1Primary stroke hospitals (PSHs)-without-endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) was a hospital that did not conduct EVT during the data-collection periods. 2PSHs-with-EVT was a hospital that performed EVT less than 15 times per year or not have stroke unit with stroke specialists. 3Thrombectomy-capable hospitals (TCHs) was defined as a hospital that had stroke unit with stroke specialists (department of neurology, neurosurgery, and rehabilitation medicine) and conducted EVT more than 15 times per year.

The Correlations of Patient- and Hospital-level Characteristics With the 30-day and 1-year Case-fatality Rates

As shown in Table 3, the 30-day CFR was significantly higher among older patients (odds ratio [OR], 1.02; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02 to 1.03), those with comorbidities (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.26 to 1.36), and those with a higher NIHSS (OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.16). Similarly, the 1-year CFR was significantly higher among older patients (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.07), those with comorbidities (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.42 to 1.53), and those with a higher NIHSS score (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.13 to 1.14). In contrast, the CFR was significantly lower in female than in male (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.68 to 0.76). With respect to hospital classification, TCHs showed significantly lower risks for the 30-day CFR (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.76 to 1.12) and the 1-year CFR (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73 to 0.96) compared to PSHs-without-EVT. However, PSHs-with-EVT did not show a significant difference in the CFR from PSHs-without-EVT.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the association between hospital classification (according to the annual case volume of EVT and structural indicators) and the CFR of AIS patients in the Korean national audit database. We found that TCHs, which recorded high annual EVT case volumes and had dedicated stroke units and stroke specialists (in the fields of neurology, neurosurgery, and rehabilitation medicine), demonstrated better 1-year CFRs in potential EVT candidates. In contrast, PSHs-with-EVT, which recorded low annual EVT case volumes or did not have stroke units or stroke specialists, exhibited no significant difference in the CFR compared to PSHs-without-EVT, the latter which performed no EVTs during the data collection period. Based on these results, AIS patients with moderate-to-severe neurological deficits should be treated in TCHs in order to improve the odds of a good prognosis; to this end, it is necessary to identify TCHs by region. The annual EVT case volume could be used as one of the primary indicators in determining these regional TCHs.

Stroke outcomes are determined by both patient-level and hospital-level characteristics [37]. In this study, the hospital classifications (PSHs-without-EVT, PSHs-with-EVT, and TCHs) reflected hospital-level characteristics. These classifications were defined by annual EVT case volume and structural indicators (stroke unit and at least one specialist in each of the departments of neurology, neurosurgery, and rehabilitation medicine) (Tables 1 and 2). Multilevel analysis revealed that at hospitals with low EVT case volumes, the quality of treatment was low for resource-demanding treatments such as EVT (Table 3). This may also be influenced by other hospital-level characteristics, such as the number of beds [37]. In other words, these findings show how hospital-level characteristics affect the outcomes of AIS patients.

The annual volume of EVT has been known to be associated with a favorable prognosis in AIS [25–28]. Several studies have suggested new cut-off values for the annual volume of EVT [26–28]. In this study, 15 case/y was used as the cut-off, which is the criterion for certifying a thrombectomy-capable stroke center in the United States [16]. In addition, a recent volume-outcome study based on Korean data confirmed that the cut-off 15 case/y was also appropriate to apply to the Korean situation [29]. However, this requirement of at least 15 EVT case/y is a minimum standard, which alone does not deliver improved outcomes for AIS patients. When hospitals were classified based (partly) on annual EVT case volumes, instances were found of hospitals that performed more than 15 EVTs/y that did not have reduced 30-day and 1-year CFRs (Supplemental Materials 1 and 2). The data from PSHs-with-EVT show that performing ≥EVT 15 case/y without appropriate facilities and human resources may still result in low treatment quality (Table 3).

The organization of integrated stroke care has been shown to improve stroke outcomes [19,38]. To redesign the SSOC for EVT application, it is necessary to evaluate the quality of acute stroke care and to qualify TCHs. As shown in our study, potential EVT candidates were reported to benefit more from TCHs than from PSHs-with-EVT or PSHs-without-EVT. It is beneficial for AIS patients to be transported directly to a TCH, even if it is located farther away than a more nearby PSH [18,39,40]. Our study may contribute to redesigning the SSOC by presenting the possibility of using annual EVT case volume as one of the primary indicators for qualifying TCHs.

This study has several limitations. First, this study used national stroke audit data between 2013 and 2016, which included periods before and after EVT was performed in clinical practice. For this reason, the study population included not only those who received EVT, but also patients who were comprehensively defined as EVT candidates (i.e., those who could be judged as needing EVT during patient transport). Second, EVT candidates included patients transferred from other hospitals and patients who may not have had LVO. The ASQAP did not collect information about the existence of LVO, which is the exact eligibility criteria for EVT. As EVT candidates may include moderate-to-severe neurological deficits without LVO, the true impact of TCHs could be underestimated compared to targeting patients with LVO. In most circumstances, decisions to bring patients to the nearest PSH or TCH were often made before confirming LVO with an imaging test. The results of the study showed that the potential EVT candidates who were transported to TCHs had better results than those transported to PSHs with or without EVT. Third, the composition of age and NIHSS severity varied by hospital classification (PSHs-without-EVT, PSHs-with-EVT, and TCHs). PSHs-without-EVT, which had a higher CFR than TCHs, had the largest number of patients over 80 years of age (45.1%), and the proportion of patients with NIHSS scores of 21–42 was 18.5% higher than that in PSHs-with-EVT and TCHs. Thus, there may have been residual confounding even though measures were taken to account for these significant variations in age and severity. Fourth, the data on hospital characteristics data were limited, insofar as it was not considered whether or not a regional stroke center existed.

In conclusion, this study showed that when AIS patients suspected to have moderate-to-severe neurological deficits were treated in TCHs, the 1-year CFR was significantly reduced. The results suggest the need to improve the existing SSOC by implementing a regional organization of TCHs and establishing a transport system centered on them. Once regional cerebrovascular centers are established for each of the 70 Hospital Service Areas (HSAs) under the Regional Health and Medical Services Plan, the annual EVT case volume may be used as one of the indicators to define TCHs within HSAs. Beyond the identification of regional TCHs, the mothership model of transferring EVT candidates directly to a TCH rather than to the nearest PSH may be a practical option for redesigning stroke treatment systems in each HSA.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS

Supplemental materials are available at https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.22.318.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Park EH, Hwang SS, Kim BJ, Bae HJ. Data curation: Yang KH, Choi AR, Kang MY. Formal analysis: Park EH. Funding acquisition: None. Methodology: Park EH, Hwang SS, Oh J, Subramanian SV. Validation: Park EH, Hwang SS, Kim BJ, Oh J, Bae HJ. Visualization: Park EH. Writing – original draft: Park EH. Writing – review & editing: Park EH, Hwang SS, Kim BJ, Oh J, Subramanian SV, Bae HJ, Yang KH, Choi AR, Kang MY.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.